Based on sociological research conducted using the Kherson community online research panel

Cumulatively from July 2023 to September 2024, a group of researchers from among the experts of the NGO “Kherson Regional Branch of the Sociological Association of Ukraine” and the New Image Marketing Group, commissioned by the Kherson City Community Foundation “Zakhyst,” conducted 32 sociological public opinion surveys.

General conclusions and results

One of the first findings of the research project was the phenomenon of unity of the Kherson urban community. It turned out that despite the departure of more than two-thirds of the city’s population, Kherson residents continue to live in the same information field, browse the same social networks and websites of their hometown every day, and adhere to a fairly similar position on most various issues. Noticeable discrepancies in the responses between those remaining in Kherson and those who have left for another country or another region of Ukraine were rather an exception to this rule and were recorded only for some items in our surveys. To this should also be added the fact that the vast majority of internally displaced persons declared a willingness to return to Kherson as soon as it becomes safe.

But at the same time, we have observed the emergence of centrifugal tendencies. Some of the displaced people have already managed to adapt quite successfully in their new places of residence, increase their income, and improve their social status. Their motivation to return is decreasing. Moreover, the more time passes, the more irreversible migration processes become. The experience of other military conflicts and large-scale displacements of people have shown that a significant number of migrants will no longer be able or willing to return, even if they now sincerely desire to do so.

The risk of the non-return of the pre-war population is a serious challenge for Kherson, since people are the main resource for the city’s future revival. Therefore, restoring the migrants’ emotional connection to Kherson and supporting community unity is an important social task. This can be achieved through methods of remote involvement in the city’s public life in such a way, that even from other regions or countries, Kherson residents can influence social processes in the community and express their opinions. It is significant that the people of Kherson themselves support such initiatives as much as possible.

An important characteristic of the Kherson community is also a strong urban identity. At the same time, local patriotism and national patriotism are not mutually exclusive, on the contrary, being intrinsically interwoven. Actually, pride in the city and in one’s Kherson identity is primarily connected with the “Ukrainian invincible Kherson.” The residents of the community are equally proud of being Kherson residents and of being Ukrainians. Other local identities (related mainly to the sense of belonging to a region – the South, the Kherson region, or the Tavria region) are not priorities. The city of Kherson is much more significant for its community. If respondents did lean toward a regional or oblast (non-urban) identity, it was almost always the second or third choice.

Urban identity to a great degree influences perceptions of desired memory politics. Kherson residents tend to organically combine the symbolism of different eras of the city’s history. For example, most Kherson residents support the idea of a joint memorial in the Park of Glory, dedicated to the memory of the fighters for Ukraine in the Liberation Struggles of 1917-1922, World War II, and the ongoing Russo-Ukrainian war. While generally approving of initiatives to decolonize toponymy and rename streets, city residents are more inclined to local and neutral names, or returning to older pre-Soviet names, provided they do not hold any imperial meaning.

The war and its associated challenges have also significantly enhanced the role of volunteerism in the community. Currently, civil society organizations are among the most authoritative institutions in Kherson. Kherson residents not only highly appreciate the work of volunteers, but also actively participate in charitable activities, help others, or donate.

Despite high resilience and belief in victory, war fatigue is gradually accumulating in the community. Residents of Kherson are directly suffering from bombing, and the number of those who have experienced the death of relatives and loss of property has increased significantly over the year. There have been more difficulties with employment. Many people have been forced to change jobs to less well-paid and prestigious ones. Those who left Kherson have also faced problems. Although, on average, they are in a better financial and psychological situation than those who remained.

Overall, most Kherson residents now feel unhappy. Most alarming is that the respondents’ condition has tended to worsen over the past year. Ultimately, psychological depression is reflected in one’s health. Very few Kherson residents can consider themselves completely healthy.

Psychological exhaustion is also manifesting itself in the fact that people have started unsubscribing from Telegram channels (in addition to the fact that the dangers of Telegram are currently being discussed). One can assume that in this case a kind of “safeguard” is set off to protect the psyche from burnout. Many respondents watch the news from the front not even daily, but hourly – taking everything that happens to heart. Despite everything, Kherson residents are not losing optimism and believe in positive changes: they associate the future with the words “hope” and “expectation of improvement.”

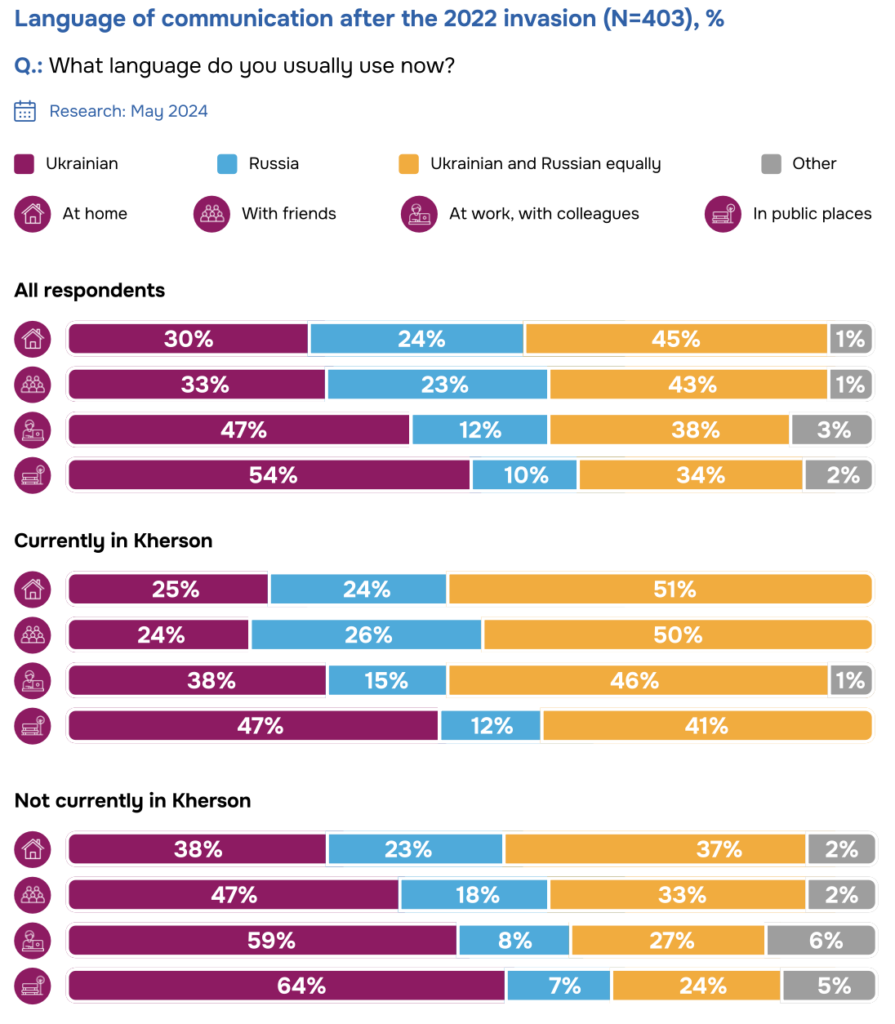

One of the visible results of Russia’s invasion and 8-month occupation of the city was that the predominantly Russian-speaking (before the war) Kherson community switched to Ukrainian in everyday communication, or at least has declared doing so. The linguistic behavior of Kherson residents became a form of resistance to the invaders and a defense of their own identity.

Kherson residents would like to dedicate a special museum to the events of 2022, and a fairly significant proportion of residents are ready to share their own stories, exhibits, or photographs for this purpose. They see the core themes of such a museum as the public resistance of 2022 and the overall resilience of Kherson.

The thought is quite widespread that the Kherson of the future will be a different city – not the one it is right now or was before the war. Clearly, the respondents imagine the renewal of Kherson differently. Everyone fills the idea of a “new city” with their own meaning, but in general, it can be stated that the demand for creating a new one is much stronger than restoring the old one.

You can read the full report by downloading it:

This research was conducted by the Zakhyst Kherson Community Foundation Charitable Organization as a part of its project implemented under the USAID/ENGAGE activity, which is funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and implemented by Pact. The consents of this research are the sole responsibility of Pact and its implementing partners and do not necessary reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government

Reproducing and using any part of this product in any format, including graphic and electronic, copying or any other usage is suitable to reference to the source.